Overview

Broadly speaking, there are three main themes of my research:

- Galaxy formation and evolution: I study how galaxies form and evolve using observational tools. Understanding the physical processes that form the galaxies and set their evolution has been one of the central problems in astronomy. With the advent of advancements in computer simulations combined with powerful telescopes, we have slowly started to uncover the hidden mysteries of our vast universe. Recent large-scale cosmological simulations have revealed that the galaxies are surrounded by a diffuse gaseous halo, known as the circumgalactic medium (CGM). Understanding the interplay between different gas flows (outflows and inflows, also known as the cosmic baryon cycle) in this invisible medium is the key to a clear and accurate picture of the fate of galaxies. In a broader sense, I want to understand the -

- Physical processes that govern the formation and evolution of galaxies and their environment.

- the complex nature of the gas flows in the CGM and how they depend on and impact the galaxy properties and its environment.

- Nature and evolution of metals in the universe using absorption line studies.

Cosmic Metal Evolution with Large Spectroscopic Surveys: Metals—elements heavier than helium—are forged in stars and dispersed into the universe through energetic processes such as supernovae and galactic winds. Tracing their abundance and distribution over cosmic time provides critical insight into galaxy formation, feedback processes, and the chemical enrichment history of the universe. My research focuses on measuring how metal mass densities evolve by analyzing absorption features in the spectra of distant quasars, using data from some of the largest spectroscopic surveys to date.

- Machine Learning and Data Science Methods: Astronomy is an observational science that relies on extensive data gathered from telescopes worldwide to study celestial objects. Analyzing these vast amounts of data requires a wide array of methods and techniques to extract scientific insights. I am deeply interested to developing and learning new data analysis tools and incorporating them into my research. I utilize classical machine learning and statistics-based methods to create efficient algorithms for modeling astronomical spectra and measuring their physical properties. I am a regular developer or contributor to several GitHub codebases -

- qsoabsfind: Absorption feature finder in astronomical spectra (Developer)

- redrock: Redshift fitter for DESI (making largest 3D map of the universe) (Contributor)

- desispec: Spectral reduction and extraction codebase for DESI (Contributor)

- desihub: Public codebase associated with the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) (Member & Contributor)

Galaxy formation and evolution

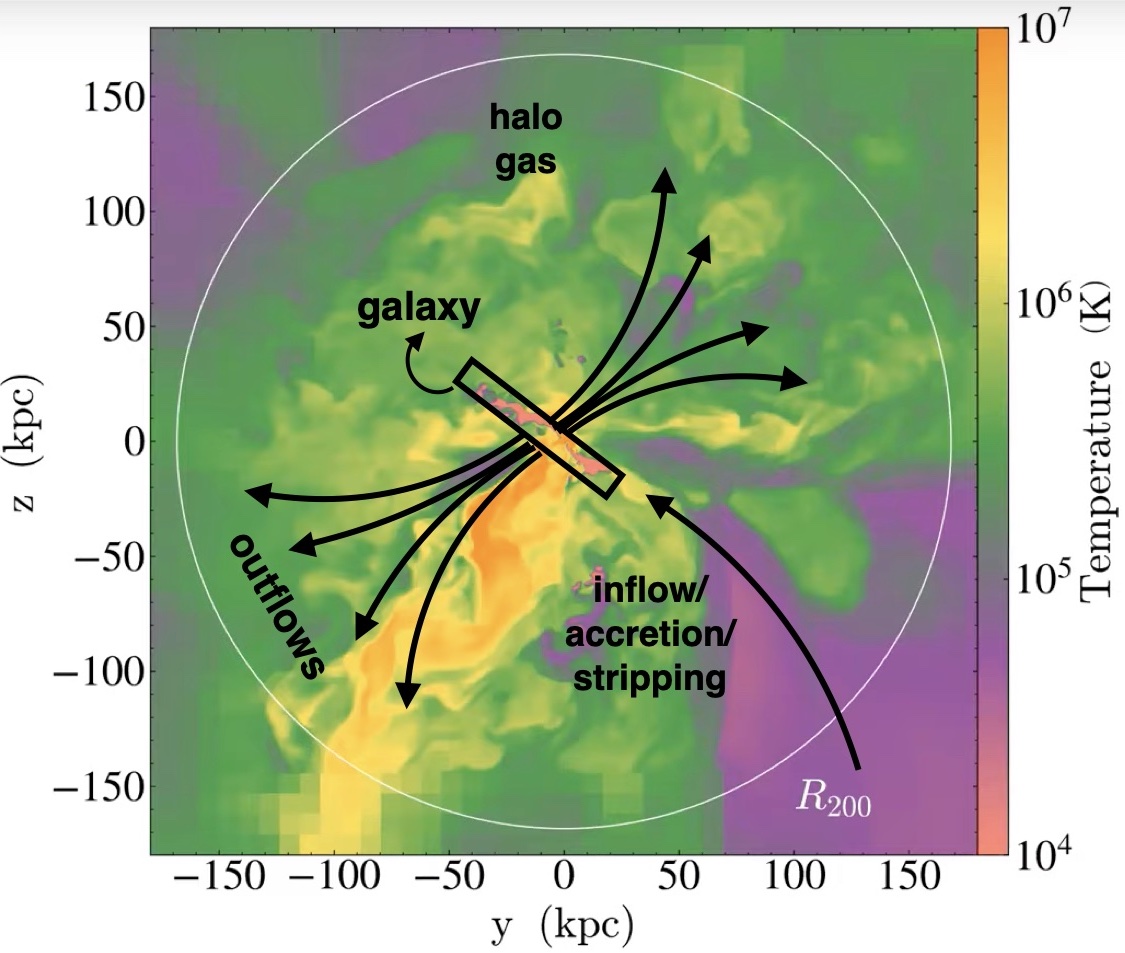

Cosmic Baryon Cycle

In simple terms, the “cosmic baryon cycle” is very similar to how evaporation and rain work on the earth. We all know that the sun heats the water on Earth, which evaporates and goes up and condenses to form clouds that shower rain on Earth. This process continues, and we call it the water cycle in hydrology. Similarly, the pristine gas (mostly hydrogen and helium) is accreted (also known as the inflow) by the galactic halo (CGM), where it forms gaseous clouds (a very complex physical mechanism) which fall on the galactic disk, where it is turned into stars. Finally, these stars release a lot of energy via supernovae or stellar winds, which kick gas out of the galaxy into the halo (CGM) (known as the galactic outflows, see Figure below, right). This process also makes the CGM very multiphase, where gases with different temperatures and densities compete. Will the galaxy continue getting fuel and forming new stars, or will it stop forming stars, depending on the balance between these gas flows? However, predicting or fully understanding the fate of galaxy formation is very challenging!

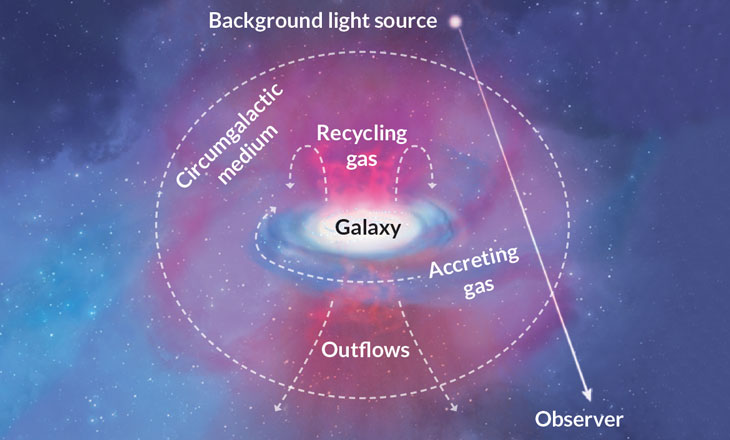

Multiphase Circumgalactic Gas Around Galaxies and Clusters in Observations

As described above, the CGM plays a pivotal role in galaxy formation, but it is very challenging to study it observationally. The CGM is very diffuse (having low densities, $n\sim 10^{-3} \,cm^{-3}$, for comparison, air density on earth is about $10^{19} \,cm^{-3}$) and the temperature can range from $\sim 10^4\, K$ to $10^7\, K$, therefore it is exceedingly hard to observe in emission as emission flux is directly proportional to the gas density. However, with the advent of groundbreaking space and ground-based telescopes, it can be studied in absorption against a bright background object.

In my PhD thesis, I explored the nature of the complex gas flows in the galaxies’ circumgalactic medium (see figure at the top) using absorption lines detected in the spectra of background Quasars. My goal was to constrain the physical properties of these gas flows with the absorption lines that trace different phases in the CGM. The setup is the following, when the light emanating from a bright background source (e.g., quasar) passes through the CGM of a foreground galaxy, it can get absorbed and cause absorption dips in the spectrum at redshifts smaller than the quasar redshift.

The different absorption lines can trace different phases and physical processes in the CGM and help us understand their connection to galaxy properties and their environment. For e.g., MgII (Mg$^{+}$, it’s a doublet line transition with wavelengths 2796 and 2803Å) and FeII (Fe$^{+}$, multiple lines) are tracers of the cold phase ($T \sim 10^4\, K$) of CGM, while CIV (C$^{3+}$, a doublet line transition with wavelengths 1548 and 1550Å) traces the warm-hot ($T \sim 10^5\,K$) CGM. In my thesis, I explored the nature and origin of MgII absorbers in the CGM of star-forming and passive galaxies as well as in galaxy clusters by characterizing their spatial distribution. Understanding the connection between this gas and the galactic properties and its environment provides more insights into the physical processes governing galaxy formation and evolution.

Below are some of my works in this field.

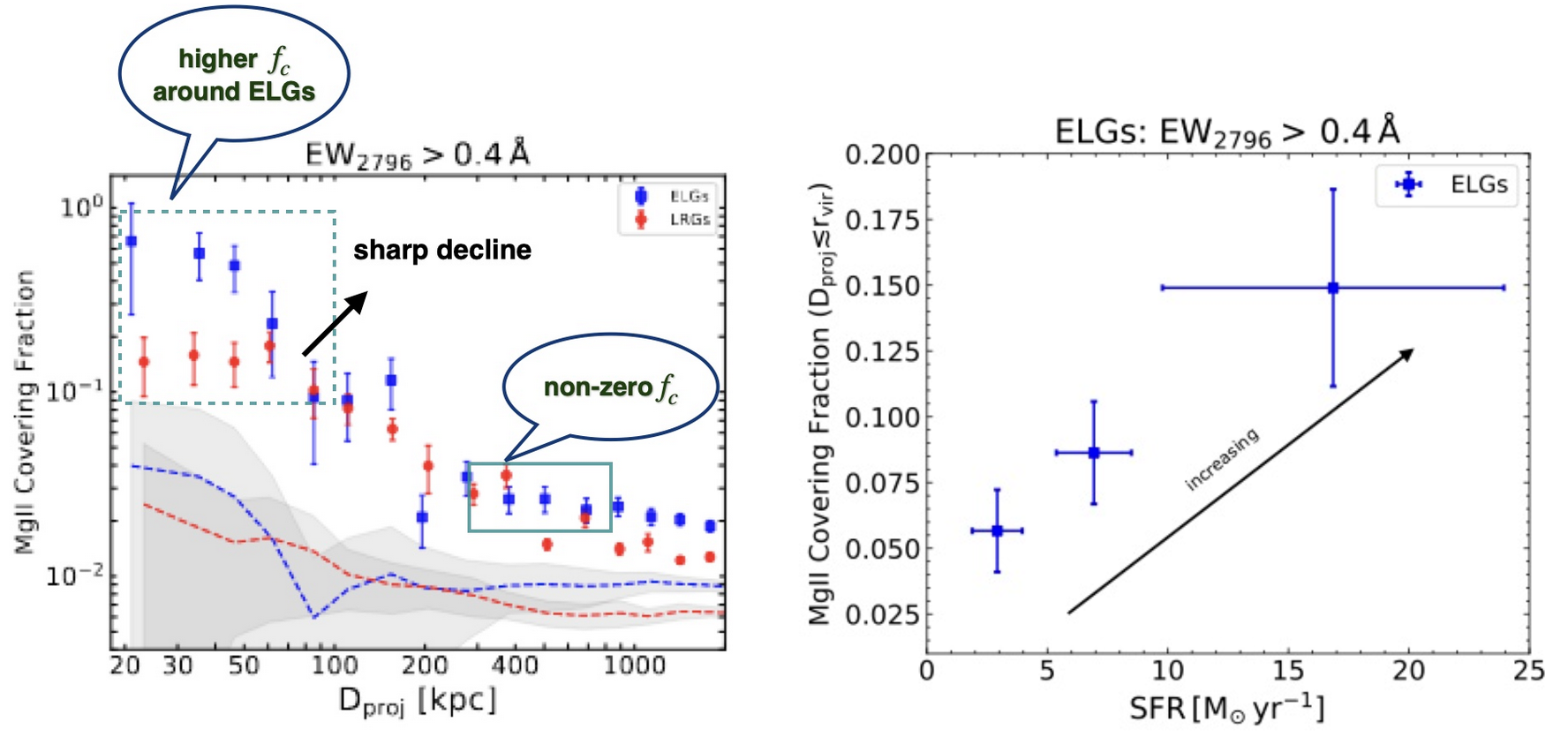

1. Characterizing cool circumgalactic medium of galaxies

In (Anand et al. 2021), I connected MgII absorbers with CGM of emission-line galaxies (ELGs or star-forming) and luminous red galaxies (LRGs or passive) from the SDSS DR16 to characterize the properties of cold gas in their CGM. With a very robust statistical analysis, our study implied that cool circumgalactic gas has a different physical origin for star-forming versus quiescent galaxies. We find that both MgII absorption and its covering fraction are 2 - 5 times higher in the CGM of ELGs than LRGs within ~ 50 kpc from the galaxy. Also, there is a very sharp decline in the covering fraction for both kinds of galaxies, and at large distances, they are within the error bars (see the left Figure). The rapid decline in the covering fraction at ~ 50 kpc implies that MgII properties are regulated by galactic outflows in the inner part of the CGM. At the same time, it is tightly linked with the dark matter halo in outer regions.

We also find that the stellar activity of ELGs plays a very important role in enriching their CGM, where the MgII covering fraction correlates strongly with the star formation activity (SFR) of the galaxy (see right Figure). In addition, we also see that MgII is rarely detected in the massive halos. The relative line-of-sight (LOS) velocity analysis also supports an outflow origin of MgII gas in ELGs, where the velocity dispersion of the absorbing cloud relative to the halo is similar to the virial velocity of the dark matter halo. On the other hand, it is suppressed by 40-50 % in the LRGs, suggesting a different origin of MgII gas in their halo, possibly accretion or stripping from the neighboring halo. To summarize, our analysis, combined with previous studies, implied that cool circumgalactic gas has a different physical origin for star-forming versus quiescent galaxies.

2. Tracing cool metal gas in galaxy clusters

In Anand et al. 2022, I extended the MgII absorber study to galaxy clusters. In this high mass regime (see Figure on left), we have the potential to shed light on the role of the environment in shaping the CGM of galaxies. Cluster halo gas known as the intracluster medium (ICM) is heated up to high temperatures ($T \sim 10^7 - 10^8$ K) due to gravitational collapse. In addition, outflows powered by supermassive black holes in the center of clusters can also heat the gas. The hot ICM emits mostly at X-ray wavelengths due to radiation from thermal bremsstrahlung produced in the highly ionized gas. Although the ICM is hot, cold/cool gas has sometimes been detected in and around clusters. The most frequently observed elements are hydrogen (Hα, Lyα) and metal absorption lines (MgII, OVI), which are detected in the spectra of background quasars.

The absorber-cluster cross-correlation study using our MgII absorber catalog and galaxy clusters from the legacy survey imaging of Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) data release (DR8) is one of the most extensive such studies to date, with $160,000$ MgII absorbers and $72,000$ clusters with spectroscopic redshifts. I characterized the nature and origin of MgII absorbers in galaxy clusters, where most of the intracluster medium (ICM) is mainly filled with hot plasma ($T\sim 10^7$ K).

Despite the hot ICM, our analysis shows a significant covering fraction ($3-5\%$) of cold gas ($T \sim 10^4$, traced by MgII absorbers) in cluster environments on virial scales. On the other hand, the surface mass density (see Figure on left) of MgII absorbers is $2-3$ times higher in clusters than in luminous red galaxies (LRGs). However, the surface mass density is $5-10$ lower than that of emission-line galaxies (ELGs). While the covering fraction of cool gas in clusters decreases with increasing mass of the central galaxy, the total MgII mass within $r_{500}$ is nonetheless $\sim 10$ times higher than for SDSS LRGs. The MgII covering fraction/surface mass density versus impact parameter is well described by a power law in the inner regions and an exponential function at larger distances. The characteristic scale of the transition between these two regimes is smaller for large equivalent width absorbers ($EW > 1Å$), implying a different origin of weak and strong absorbers in dense environments.

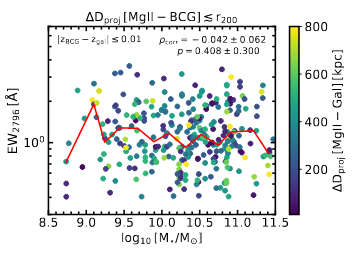

Furthermore, I also investigated the connection between MgII absorbers and the member galaxies of the cluster. Cross-correlating MgII absorption with photo-z selected cluster member galaxies from DESI reveals a statistically significant connection. The median projected distance between MgII absorbers and the nearest cluster member is $\sim200$ kpc, compared to $\sim 500$ kpc in random mocks with the same galaxy density profiles. We do not find a correlation between MgII strength and the star formation rate of the closest cluster neighbor (See figure on the right). This suggests that cool gas in clusters, as traced by MgII absorption, is (i) associated with satellite galaxies, (ii) dominated by cold gas clouds in the intracluster medium rather than by the interstellar medium of galaxies, and (iii) may originate in part from gas stripped from these cluster satellites in the past.

3. Multiphase Halo Gas of Star-Forming Galaxies at $z \sim 1.5$

Currently, I am using a combination of quasars and intermediate-redshift $z\sim 1.5$ galaxies to study absorption produced by cool and warm gas, traced by Mg II and C IV absorbers, respectively. To enable this, I am developing a stacking-based method to detect faint absorption signals in quasar spectra using data from the DESI experiment (Anand+ in prep.). Previously, the lack of a sufficiently large galaxy sample at this key redshift made such a study unfeasible. This work will help fill that gap and provide new insights into the multiphase circumgalactic medium around star-forming galaxies at cosmic noon.

Cosmic Metal Evolution with Large Spectroscopic Surveys

1. Understanding the evolution of CIV absorbers in the universe using large cosmological surveys

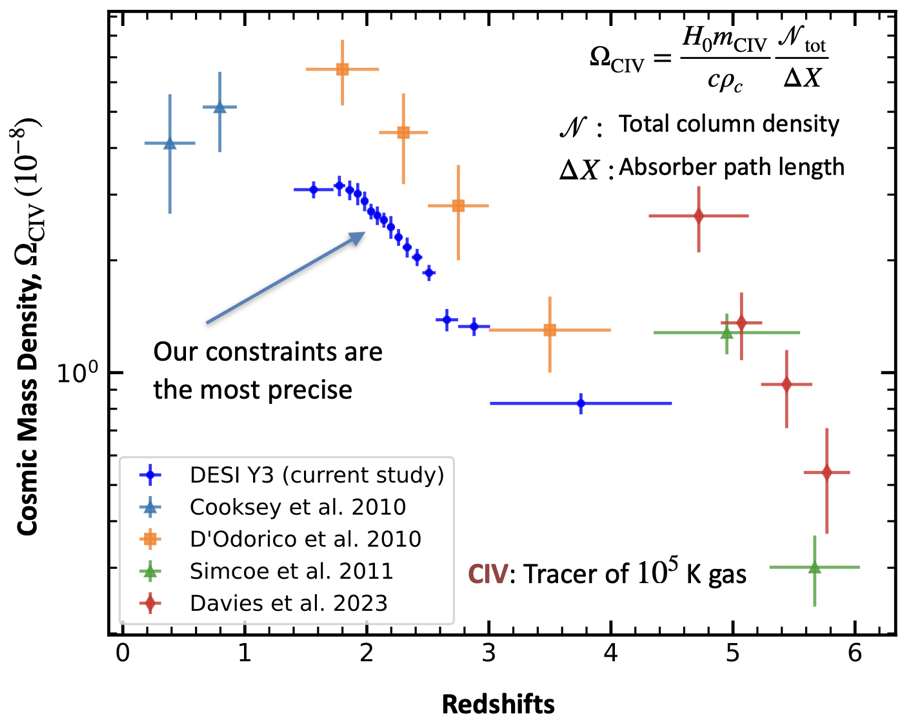

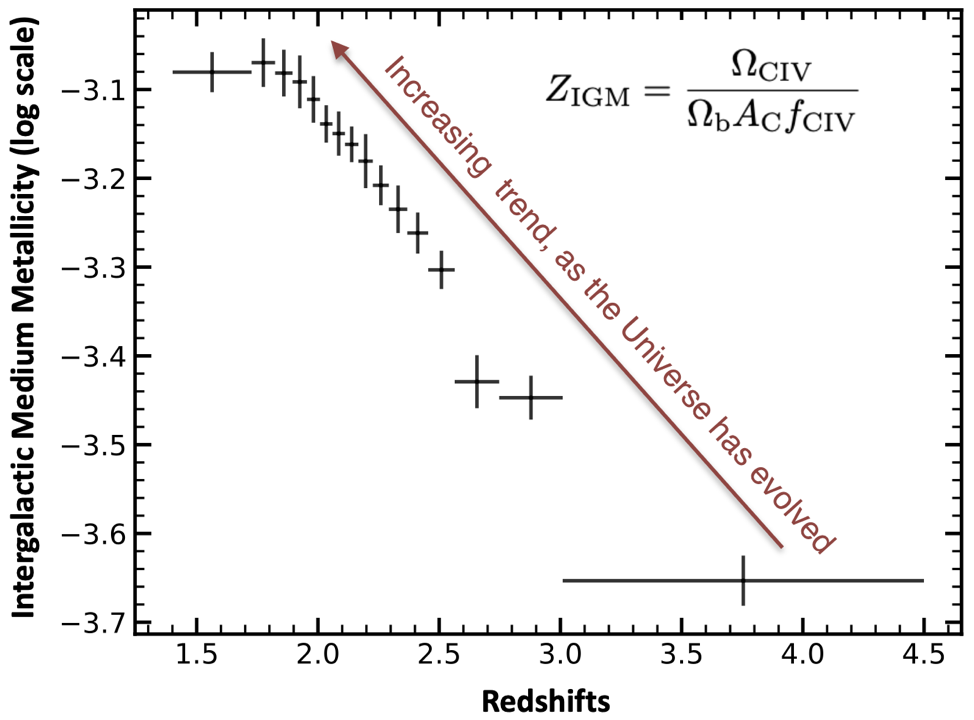

Recently, I led a project (Anand et al. 2025) to identify thousands of C IV absorber systems in quasar spectra from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) survey. Using a large sample of over 300,000 quasars, we constructed the most extensive catalog of C IV absorbers to date—comprising more than 100,000 systems. By measuring the redshift, equivalent width, and column density of each absorber, we provided the tightest constraints yet on the cosmic mass density of C IV and the intergalactic metallicity it traces, over the redshift range $ z = 4.5 $ to $z = 1.4 $ —spanning nearly 3 billion years of cosmic time.

Our analysis revealed that the abundance of triply ionized carbon increased by a factor of $\sim 3.8$ as the universe evolved. Interestingly, this redshift-dependent trend closely mirrors that of He II photoheating, hinting at a shared origin driven by galaxies and quasars that power the cosmic ultraviolet background (UVB). This work highlights the critical role of galaxies and AGN in ionizing carbon to high states in the intergalactic medium (IGM). Our catalog will serve as a valuable resource for future studies of galaxy–absorber correlations, especially around $z \sim 1.5 $ —a key epoch near cosmic noon—offering new insights into the warm-phase gas in galactic halos and the cosmic metal cycle.

2. A comprehensive analysis of metal mass densities in the Universe

In another ongoing work (Anand+ in prep.) that I am leading, I am expanding the cosmic mass density analysis to several metal species. My goal is to present the most comprehensive analysis of the cosmic evolution of metal mass densities in the Universe from ( z = 4.5 ) to ( z = 1.4 ) using large spectroscopic surveys. I will provide the tightest constraints on the metallicity in the IGM for the first time using survey data.

Machine Learning and Data Science Methods

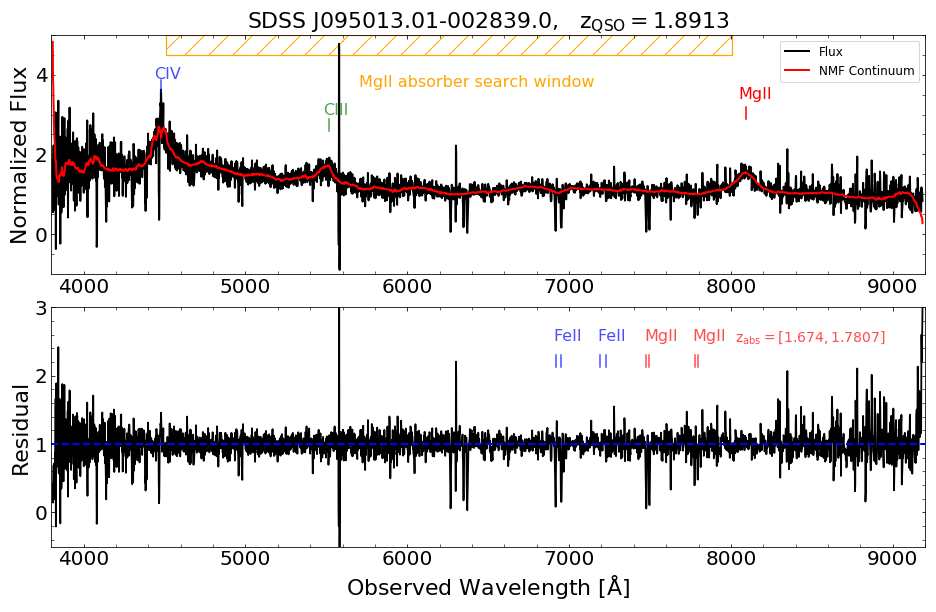

1. nmfqsofit: NMF-based Quasar Continuum Fitter

Modeling quasar continua is an important challenge in quasar absorption line analysis. In (Anand et al. 2021), I developed an automated pipeline, nmfqsofit, that models the intrinsic continuum of quasars detected in low-resolution spectroscopy. The pipeline is highly parallelized and optimized, enabling the processing of thousands of quasar spectra within minutes.

The pipeline employs a dimensional reduction technique known as Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF), which decomposes the quasar intrinsic emission features into eigenvalues and eigenspectra to model the quasar continuum. I built high-fidelity NMF eigenbasis vectors using SDSS DR16 quasars that can be used to construct continua for any SDSS-like quasar spectra (e.g., DESI, WEAVE). It has been tested and validated on $\sim 1$ million quasars from SDSS DR16 and $ \sim 0.5$ million quasars from DESI. See the red curve in the figure above.

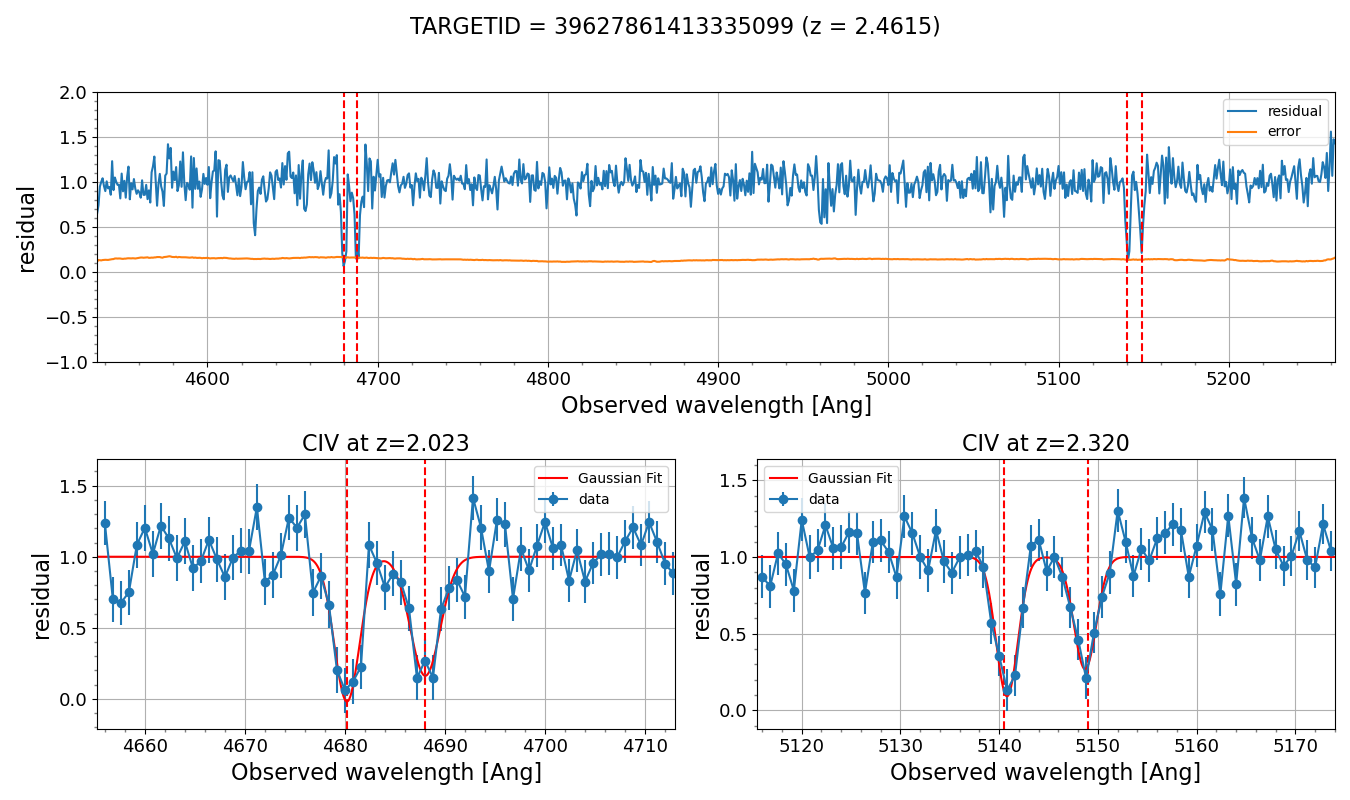

2. qsoabsfind: A Python Package for Detecting Absorption Line Doublets in Low-Resolution Quasar Spectra

qsoabsfind is a robust and highly efficient Python-based pipeline designed to identify absorption line doublets in low-resolution quasar spectra such as those from SDSS and DESI. It employs a matched-kernel convolution algorithm combined with adaptive signal-to-noise criteria, enabling automated detection of metal absorbers in thousands of quasar spectra within minutes. The code is optimized for parallel processing and supports batch-mode analysis on HPC clusters or single-node setups.

The pipeline is generic and flexible, capable of detecting a wide variety of doublet systems including C IV, Mg II, Fe II, O VI, Si IV, Al III, and N V. In addition to detection, the code offers built-in support for defining dynamical search parameters, wavelength windows, equivalent width measurements and estimating column densities using the apparent optical depth (AOD) method, making it suitable for a broad range of astrophysical studies involving intergalactic and circumgalactic gas.

The qsoabsfind pipeline has been used in several large-scale absorption line surveys:

- Mg II and Fe II absorber catalog from SDSS DR16 quasars, comprising over 160,000 absorbers (Anand et al. 2021).

- C IV absorber catalog from DESI DR1 quasars, consisting of over 33,000 systems (Anand et al. 2025), the largest C IV catalog to date.

The pipeline’s modular design allows for easy extension to new spectral datasets and absorber species. It is actively maintained and documented on GitHub, and has already become an integral part of several ongoing DESI value-added catalog efforts.

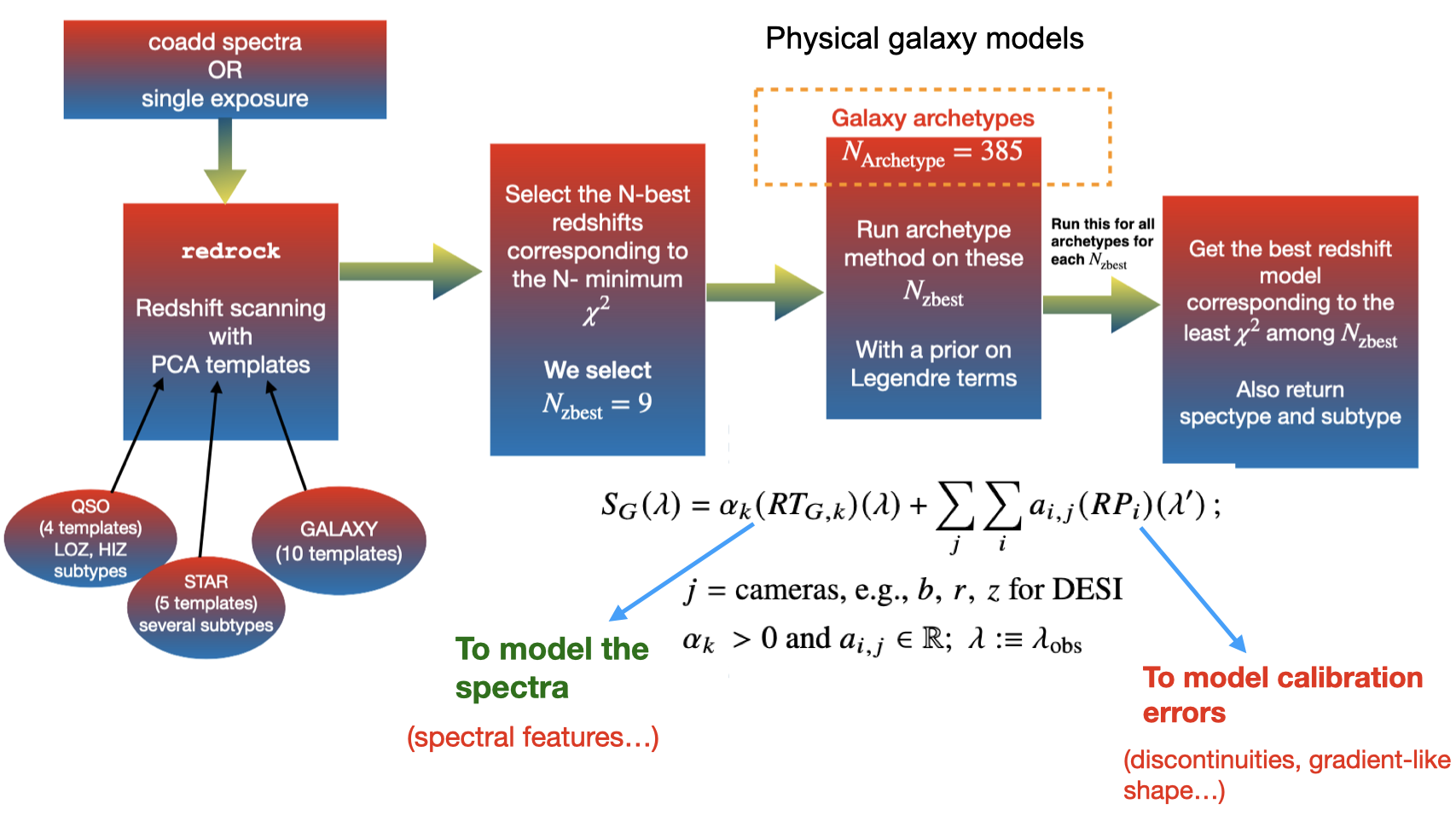

3. New methods of galaxy spectral fitting for redshift estimation

With the advent of ongoing large spectroscopic surveys, analyzing vast numbers of astronomical spectra and accurately measuring their distances has become increasingly important. As we advance toward precision cosmology, obtaining precise redshift measurements of galaxies and quasars is crucial for all major cosmological surveys. Recent surveys, such as DESI, are collecting unprecedented volumes of astronomical spectra to perform next-generation cosmological analyses, making accurate redshift determination one of the key challenges we face.

Given the extensive volume of data, manually inspecting millions of spectra to determine the best redshifts is impractical. Instead, we must rely on dimensionality reduction techniques to model the spectra of these objects. One widely used method is Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which reduces a large set of spectral features into their principal components (orthogonal eigenvectors) and reconstructs spectra using a linear combination of these components. While PCA is computationally efficient and fast, it has notable limitations—it does not consider the physical characteristics of astronomical objects, often leading to unphysical modeling or overfitting of the input spectra.

In my recent work Anand et al. 2024, I developed a computationally efficient galaxy archetype-based redshift estimation and spectral classification method (see figure above) for the Dark Energy Survey Instrument (DESI) survey. Our proposed approach improves upon this existing method by refitting the spectra with carefully generated physical galaxy archetypes combined with additional terms designed to absorb data reduction defects and provide more physical models to the DESI spectra. We test our method on an extensive dataset derived from the survey validation (SV) and Year 1 (Y1) data of DESI. Our findings indicate that the new method delivers better redshift success rates for them while reducing catastrophic redshift failure by 10−30%. At the same time, results from millions of targets from the main survey show that our model has relatively higher redshift success and purity rates (0.5−0.8% higher) for galaxy targets while having similar success for QSOs.

Although this method is slower than the classic PCA, it effectively addresses the issues of unphysical modeling and overfitting. It is also generic and can easily be extended to other upcoming surveys such as WEAVE, WAVES, and PFS on large optical telescopes. The github repository details the algorithm and code.

Past research interests and projects

During my undergraduate studies, I worked on a few other topics in astronomy. In addition to that, I also explored some topics in high-energy physics and computational nonlinear dynamics. I still like those topics and would love to explore them in the future. You can find more about my past projects here.